Titanium remains an essential element for the aerospace industry, which absorbs about half of the total global production of this lightweight metal.

And while this metal is typically not included among the so-called “rare earths” that are central to the ongoing strategic rivalry between the United States and China, securing its continued supply has long been a source of concern for Western aircraft manufacturers.

Back in July 2023 AeroTime explained how the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions had put the Titanium supply chain under strain, reinvigorated the titanium recycling market, and led to major consumers seeking alternative sources of this metal.

Two years on, let’s take another look at the state of the titanium market. Have Western aircraft manufacturers shed their reliance on Russian and Chinese aerospace-grade titanium sponge? Has new processing capacity come on stream? And what are the prospects for the titanium market?

When it comes to titanium supply chain reliability, the biggest uncertainties may actually still lie ahead, according to Nils Backeberg, Founder and Director of Project Blue, a market intelligence and research firm specializing in mineral commodities.

Speaking with AeroTime from South Africa, Backeberg noted that the disruption created by the war in Ukraine has taken place at a time in which demand was still recovering from a relative historical low.

“Even today, in 2025, we have barely recovered the prices of 2018,” explained Backeberg, who attributed this to a number of factors which have slowed down titanium demand within the course of the last five to six years.

The technical issues experienced by some aircraft programs, such as the B737 MAX, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the airline industry and, more recently, the supply chain constraints which have been felt across the industry, have all contributed to keeping aircraft production rates below their potential.

“With the Boeing MAX issues and COVID-19 we saw demand for titanium drop significantly, but more production ramped up, predominantly in China. So, we’ve actually been in a surplus market,” Backeberg explained. “And this is despite the fact that the supply chain was disrupted due to the war in Ukraine. So, demand fell before supply and then, even if demand recovered in 2023-24, supply chain issues dampened that demand and it didn’t come back as quickly as possible.”

However, Backeberg added that the soothing effect of these factors on the titanium market may soon be gone as demand is swiftly catching up.

Aircraft manufacturers are under pressure to ramp up production as orders keep piling up, driven by continuously growing demand for air travel.

According to Project Blue, there will be a requirement for more than 1.6 million tons of titanium by 2044 to meet the forecast production of the main aircraft and engine makers, which stands at about 46,000 new commercial planes over the course of the next two decades.

It is estimated that commercial aircraft will account for nearly 90% of annual titanium demand by the late 2040s.

Titanium market bottlenecks persist

Can you guess where all that titanium will come from?

“Over the last 10 years, China has invested in titanium capacity,” stated Backeberg. “If talking about titanium sponge, in 2018 China was less than 40% of global production and by 2024 we’re talking closer to 70 to 80%.”

His firm, Project Blue, has built a database of titanium mining and processing facilities, which industry players and analysts use to keep a watchful eye on this market.

“China is importing quite a lot of titanium feedstock from all over the world to do this,” Backeberg said. “They’re feeding their industrial growth. China’s busy! The last two decades investment was in steel, energy and so on. There’s still investment in energy, in renewables, but with the steel industry is reaching its capacity in China, they’re going for more valuable industries, and titanium is one of them.”

According to Project Blue data, in 2024 Russia and China accounted for 11% and 63% of the world sponge capacity, respectively, a combined 74% of the world sponge production. Likewise, China has 44% and Russia 20% of the worlds titanium melt production making up 64% of the worlds production. And when it comes to titanium mill products, China has 66% and Russia 10% of the world’s total production.

Remarkably for what has traditionally been a resource-based economy, not much titanium is actually mined in Russia. The country’s strength in this market is due to industrial processing capacities built over many decades.

This is an important point to understand when looking at why the West has yet to develop alternative sources of titanium at scale that are not controlled by its major geopolitical rivals.

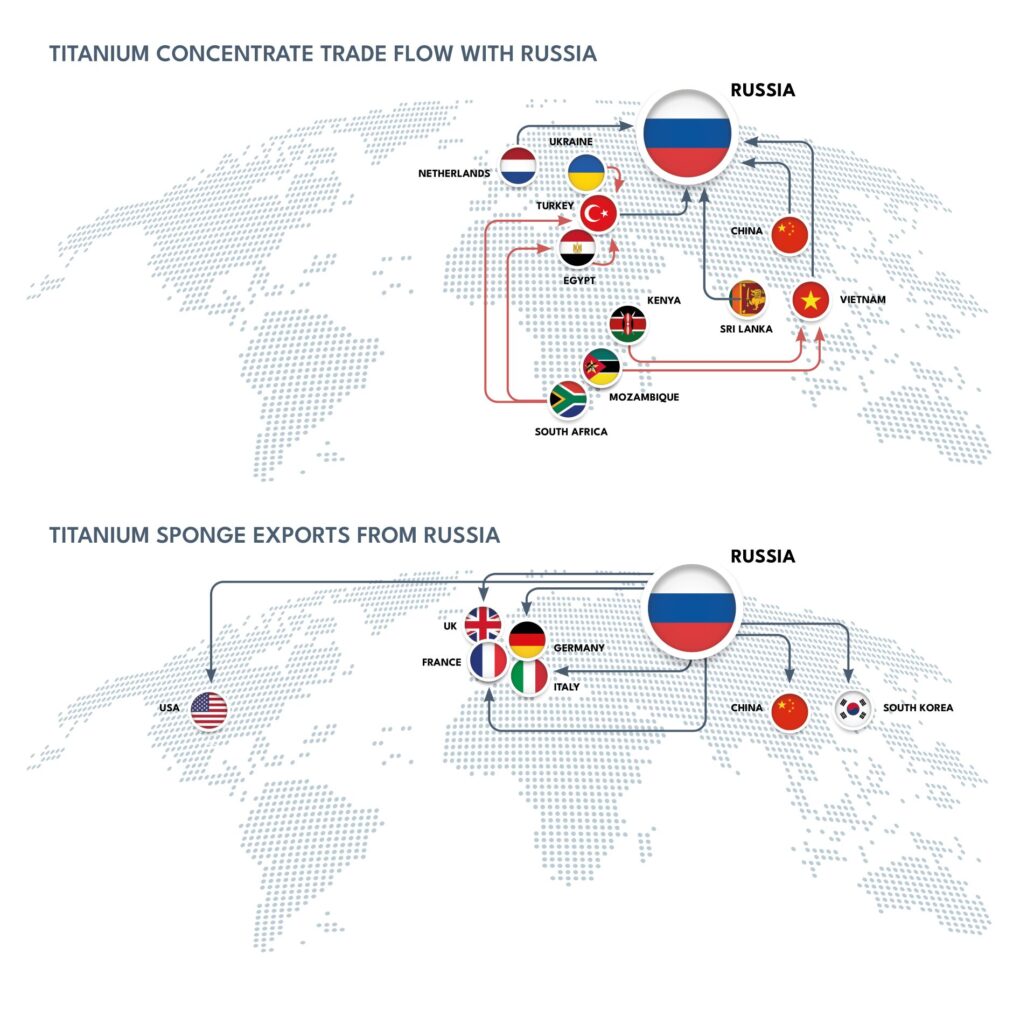

Ironically, Ukraine used to be the primary source of a large percentage of the titanium processed in Russia. In this regard, Backeberg explained that, while China has invested heavily in titanium metal production, its producers still have to upskill to aerospace grade. Russia and China are however increasing their collaboration in the production of titanium and sponge.

“If you look at the supply chains over the last couple of years, you see that China sends feedstock to Russia and receives aerospace-grade sponge imports from Russia,” Backeberg explained.

Is supply diversification a realistic proposition?

So, what can the US and Europe do in order to boost the resilience of their titanium supply chains?

“In essence, the Russian titanium supply issue can be sorted by investing in refining capacity elsewhere. But it’s not like you can start a new refinery process titanium and say, ‘here you go, put this into your aircraft’. It’s got quite a lot of regulations and certifications to go through,” Backeberg said. “It can take up to 10 years or more to be able to produce material qualified for aerospace grade applications.”

“For companies like Airbus, Boeing, Rolls-Royce, Safran, and Pratt & Whitney, the only immediately scalable, geopolitically tolerable diversification is to go to Japan, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia for titanium sponge, increasing Western melting capacity, and obtaining some marginal gains from additive manufacturing [which is essentially resorting to 3D printing, which uses less titanium but can’t replace traditional manufacturing at scale yet – ed. note],” he continued. “US sponge production revival and increasing the scale of Indian production are strategic, long-term options, not 2026 solutions.”

Airbus signed an offtake agreement with Saudi Arabia, but to get that titanium onto an aircraft is still going to take some time. The US government, through the Department of Defense (DoD), has increased funding in supporting domestic titanium supply. However, this has been focused on recycling metal scraps. The US still lacks sponge production capacity.

“There are also some titanium production projects in the US, like IperionX, but this is mainly looking at recycling off cuttings from industrial processes, what you call secondary supply from processing plants. It’s a significant volume for some uses. They are buying five times the amount of titanium that actually ends up making parts in question,” Backeberg explained. “So, there’s quite a lot of off cut material that comes back into the system and is then re-melted. But there are losses in the process, and some of the material can’t be reused for the same types of grades because it has to get re-melted and reused.”

Backeberg pointed out, though, that over time, and as 3D printing becomes more widespread, processes will become more efficient in terms of material use, and this will reduce the amount of metal shavings available for recycling.

Airbus and Boeing are so dominant in the commercial aerospace industry that so far, they have been able to navigate the geopolitical muddy waters.

However, Backeberg warned that the two Western aerospace giants have cause for concern regarding the emergence of COMAC as a major commercial aircraft manufacturer and the effect it may have on the titanium market.

He pointed out that in a market in which supply is tight, China may want to prioritize its domestic consumers and prop up its own aerospace programs.

“Last year COMAC had capacity, I think, to produce some 18 aircraft, but they’ve got thousands of orders. So, they’ve got an incentive to ramp that up! Chinese producers are upskilling themselves and we know that they can do that. They’ve done it before. They’ve done it in every other commodity.”

Backeberg noted that, while Chinese commercial aircraft maker COMAC is still small, as it grows it could start to redirect crucial feedstock coming out of Russia.

“This then becomes a geopolitical conversation,” he added. “Boeing and Airbus could be starved of Titanium.”

The same concerns apply to the engine supply chains, although in this case, in addition to titanium, there is also concern about other key metals.

Rhenium, the other key element

The sourcing of Rhenium in particular is another critical stranglehold since China has also been building up its market share in this market. The heat-resistant property of Rhenium makes it an essential component of the alloys used to make high-pressure turbine blades that go into modern jet engines. Around 80% of Rhenium global supply goes to the aerospace industry.

China’s commercial aircraft programs, such as the C919 airliner, still rely on Western-made engines, such as those made by CFM International. However, it is no secret that China is looking at developing its own engine program.

Backeberg concluded by pointing out the potential role of military demand in this story. Even if titanium’s intensity of use is relatively higher in military aircraft manufacturing, with fighter jets, for example, using more than three times the amount of titanium per kg than the typical narrowbody aircraft, it is the commercial aircraft making industry that drives the market. Commercial aerospace makes around 80% of the aviation industry demand for titanium.

However, while military and space programs are similarly at risk, their highly strategic nature may offer a way around should the supply of key metals dry up.

“The military may be able to afford investing in niche, dedicated supply chains, as they already do with some materials,” Backeberg stated “That might act as a catalyst to actually build out certain supply chains.”

The post Global titanium market at risk of tightening as China-Russia grip persists appeared first on AeroTime.